Intersection of Caste and Gender in Manual Scavenging – UPSC Sociological Perspective

September 10, 2024

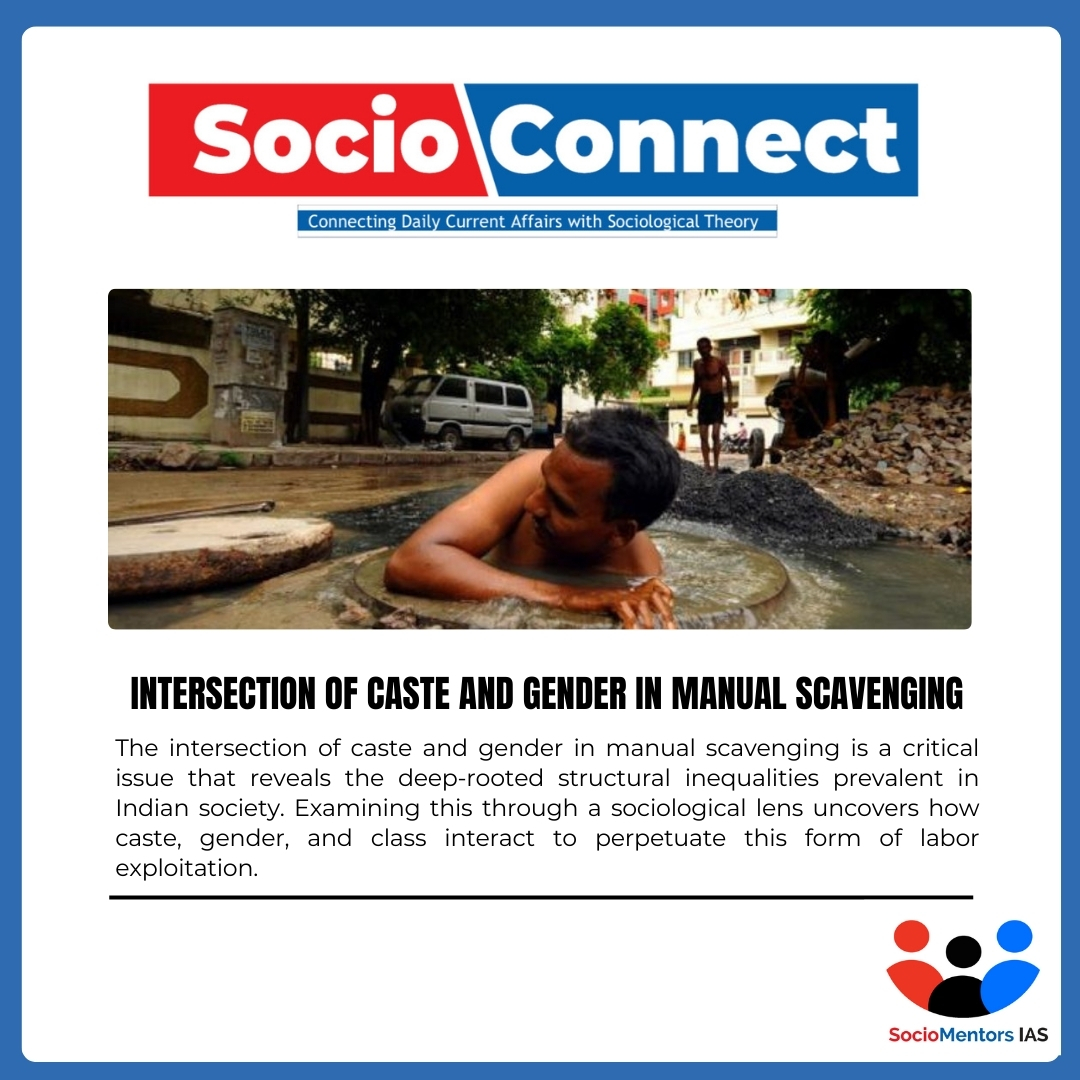

The National Commission for Safai Karamcharis, a statutory body set up by an Act of the Parliament for the welfare of sanitation workers have estimated that since January 2017 one person has died every five days on an average across the country. The intensity of the problem can be assessed by the fact that there are about 2. 6 million dry toilets that require manual cleaning (Down to Earth, 11 Sept, 2018) thus susceptibility to various infections becomes an obvious health calamity for them. Around 1. 8 lakh households earn their livelihood doing this as per the socio-economic caste census data, 2011 with highest prevalence in Maharashtra (63, 713) followed by Madhya Pradesh (23, 093) (Hindustan Times, July 12, 2015).

This life situation is more of lack of choice for an alternative employment available (Human Rights Watch, 2014)for the workers as they are trapped in a vicious circle of deprivation (poverty) and discrimination (caste). The class, status and power of the marginalised workers as unskilled labour systematically deprive them of opportunities which further lower their low caste social status into marginalised low class workers.

Why Manual Scavenging still exists in India

- Low Income and poverty of Dalits: Gail Omvedt analyzed the intersection of caste and class, noting that Dalits often remain trapped in manual scavenging due to economic exploitation and lack of viable alternatives. She argued that the caste system not only dictates one’s occupation but also limits access to education and alternative employment, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and marginalization.

- Urbanization and Informal Labour: Sujata Patel pointed out that urbanization and informal labour markets have further entrenched caste-based occupations in cities. She argued that the lack of proper urban planning and sanitation infrastructure creates a demand for manual scavenging, especially in informal settlements, trapping Dalits in these roles.

- Soft State: Gunnar Myrdal’s concept of the “soft state” describes how weak state capacity and corruption contribute to the persistence of manual scavenging. Myrdal argued that laws in “soft states” like India often exist in theory but are poorly enforced, particularly when it comes to protecting marginalized communities. For example, Rajasthan’s “Mukhya Mantri Shahari Jan Kalyan Yojana” (2022) program aimed to rehabilitate manual scavengers by providing alternative livelihoods and housing. However, reports indicated significant delays in implementation and inadequate funding, leaving many beneficiaries without the promised support.

- Caste system and rigidity: Ashish Nandy explored how cultural narratives around purity and pollution reinforce social stigma against Dalits engaged in manual scavenging. Nandy argued that these deep-rooted cultural beliefs make it difficult for Dalits to escape these occupations, as they are socially ostracized and denied opportunities for upward mobility.

- Occupational Segregation of Castes: Anupama Rao focuses on how Dalit identity is constructed and maintained through caste-based occupations. She argued that manual scavenging is not just a form of labour but a mechanism of social control that reinforces Dalit subordination and limits their social mobility.

- Defense of Tradition: Despite technological developments like Robotic sewerage cleaner, resistance to adopt such technologies shows a defense of tradition, which is often more about maintaining social hierarchies than preserving cultural heritage.

Manual Scavenging and Women

According to Human Rights Watch, of the 1.2 million manual scavenging workers in India, 95% to 98% are women, who are forced to clean dry latrines, carry loads of excrement in leaking cane baskets, clear sewage, discard placenta post-deliveries, work on railway tracks, exhume dead bodies while enduring sexual harassment, social exclusion, dismal wages, and a lifetime’s worth of trauma

- Manual scavenging women workers are from Valmiki caste, predominantly an urban Dalit community present in Punjab and national capital Delhi; Haila and Halalkhor castes in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, and from Mister and Dome castes in Bihar. Derisively, they are called “Bhangis,” which loosely translates as individuals with “broken identities.” They are untouchables among untouchables, and are located at the lowest rung of the social order, and are ostracised by Dalits themselves

- Low Wages and Exploitation: A 2014 study, which surveyed 480 women from Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh reveals that 85% of female scavengers are married women (Jan Sahas Social Development Society 2014). Some women are paid only as little as Rs 10 to Rs 20 a month along with a meal for cleaning a dry toilet during festivals. They also face sexual harassment and assault from their supervisors.

- Stigmatization: Bose says that, women who leave the occupation are still stigmatised, and are not allowed to participate in village functions, religious ceremonies, and are kept at a distance. Even if these women leave scavenging for good, the society knows who they were (Bose 2019).

- Health Issue: According to report by Rashtriya Garima Abhiyan 2018, scavenging exposes them to noxious gases, impairing their gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, respiratory, cardiovascular, and reproductive organs. They suffer from rashes, rotting of skin, permanent hair loss, nausea, breathlessness, palpitations, sore throat, loss of libido, and bear frequent infections .

- Lack of government data: There is a gross lacuna in the government data on the number of manual scavengers, and there are no specific policies to alleviate their misery and to rehabilitate them

Way Forward

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013, needs to be strictly enforced to prevent manual scavenging. Local authorities should be held accountable for ensuring compliance, and stringent penalties should be imposed on those who violate the law. Moreover the government should invest in and deploy mechanized cleaning equipment such as sewer-cleaning robots, vacuum trucks, and bio-digester toilets across urban and rural areas. These technologies should be made accessible to municipalities and local bodies to eliminate the need for human intervention in hazardous waste management.